Stepping foot on Attu

For a brief moment, I was the only person standing on the island of Attu. In my haste to jump out of the Zodiac between waves, I stood submerged in the swirling currents of the North Pacific and Bering Sea. My tightly-snapped rain pants kept the salt water from filling up my green rubber Xtratuf boots as I sloshed my way onto the beach. In June of 1942 the 301st Independent Infantry Battalion of the Japanese army landed on Attu. It wasn't hard to picture soldiers about my age standing on this same beach, wondering what surprises were hidden behind the snow covered peaks. My worst nightmare wasn't encountering unexploded ordinance, or falling into a crevasse while crossing a snow field. It was having sunny weather and no winds, which would prevent birds from the Asian continent from arriving on Attu by mistake.

My fear wasn't unfounded; the Robin's-egg-blue sky boldly defied my vision of Attu: somber skies and verdant vales blowing the wet salty air off the ocean and through the tightly-gritted teeth of every jacket zipper. The steady rain, accompanied by blowing winds and bone-chilling numbness I expected to feel were noticeably absent, replaced instead by puffy cloud banks obscuring wide views of a azure sky. With less than a dozen clear days a year on Attu, we had won the weather lottery, but our golden ticket didn't guarantee rare bird sightings. Looking forward into the week, the wind forecast improved, culminating in Southwest winds that promised a good storm. Luckily, the forecast held and we had to leave Attu early and seek harbor on the North side of Agattu, an island just south of Attu. I'll leave that story for another post.

A Goose Story

An Aleutian Cackling Goose takes flight on Attu. This species is the smaller cousin to the Canada Goose. Notice the shorter neck, and white necklace at the base of the neck.

While waiting for the Zodiac to bring the second half of the group to the island, I meandered inland away from the beach, through the knee-high tufts of grass still thawing from the damp snowdrifts that covered the higher slopes and valleys. Wavy strings of Cackling Geese flew overhead, noisily protesting our arrival on their beach. The presence of Aleutian Cackling Geese here on Attu is a conservation success story. In the 1800's Russian fur traders introduced foxes to the Aleutian Islands, in hopes of returning and harvesting fox pelts for market. Goose eggs and goslings provided easy food for the foxes, which thrived on many of the uninhabited islands. Russian trappers returned to these islands and harvested the foxes which had increased tenfold, subsisting on nesting birds. In half a century, foxes had eliminated a species which had evolved among these islands since the last Ice Age. Aleutian Cackling Geese were believed to be extinct. However, Alaskan conservation pioneer Bob "Sea Otter" Jones discovered a lost colony of Aleutian Cackling Geese on Buldir Island in the 1960's, and the Aleutian Cackling Goose became of the first species listed on the newly-minted Endangered Species list in 1967. Bob Jones spent over a decade removing foxes to help restore geese on the Aleutian islands. He captured goslings to be bred and reintroduced on fox-free islands, and trained biologists to do the field work necessary to ensure the survival of these birds. Over the next 30 years Aleutian Cackling Geese were re-introduced to fox-free islands countless times until a wild population took hold, and goose numbers began increasing exponentially. Despite his hard work and dedication to these efforts, Bob Jones never lived to see the goose removed from the Endangered Species list in 2001. Today, Cackling Geese are prolific on the fox-free Aleutian islands. Some days I found over a dozen nests, which will translate into hundreds of new goslings in a few week's time.

Camouflaged nests were scattered around the grassy hillsides, valleys, and ridges of Attu.

The Zodiac still hadn't arrived. I could tell people were ready to go birding. People paced back and forth on the beach, adjusting their gear, cleaning their binoculars, and scanning the horizon for the first rare bird of the trip. It was like watching kids on Christmas morning, eagerly waiting to open their stockings. Having arranged my gear and checking and double checking my camera settings, I hesitantly poked at a piece of metal debris on the beach, my camera in hand in case a bird flew out from underneath. Nothing. I scanned the rocky coves with my Maven binoculars in hopes of spotting a rare seabird. Only Common Eiders and Harlequin ducks popped up to the surface after feeding on mollusks. A few individuals lounged on rocks exposed by low tide, drying out in the sunlight. I still couldn't believe I was on Attu.

Lower Base, the remnant US Coast Guard building which was used by Attours to house birders in the 1980's and 90's

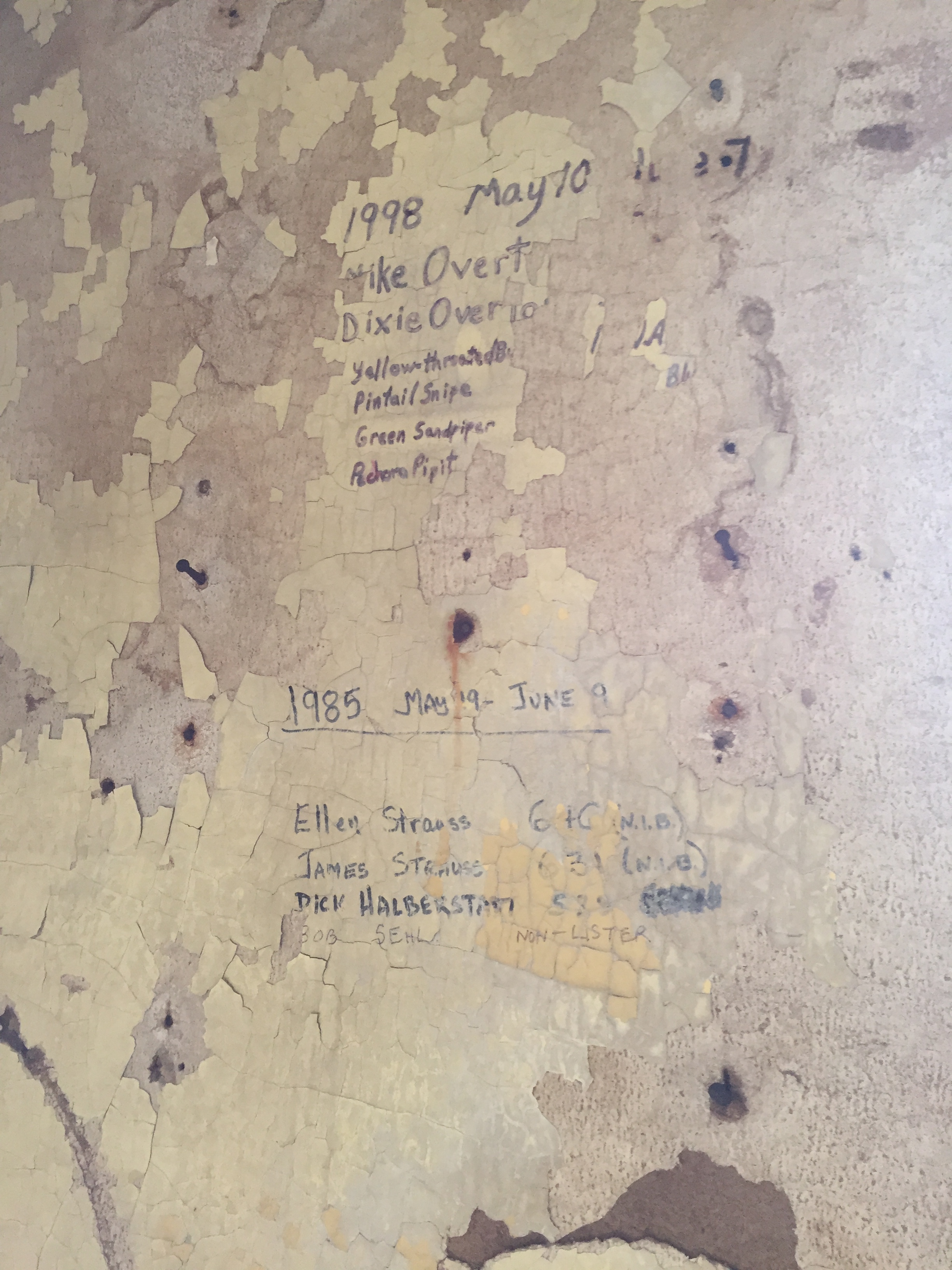

I couldn't wait any longer. Eager to spot something unusual, I explored the outside of the Lower Base building, a concrete skeleton of a building with a rich history of housing Attour birding groups. Peeking through the windows, the faded names of birders and their lists were visible on the walls, along with notable sightings from each year. The hand-written scrawl on the walls was slowly disintegrating with each passing year as the salty wind and rain erode away the wall's exterior layers.

The outline of a Raven cut in the plywood covering a window at Lower Base is one of the only outward signs of the birding history of this building.

Soon the other group had arrived on the beach, and re-enacting the same preparatory dance we had done earlier, donning our gear. Jackets were zipped, scopes with carbon-fiber tripod legs were extended, and hoods cinched down to keep the hungry wind at bay. We were ready to bird Attu.

Want to visit Attu in 2017? Now you can! Visit Z Birding Tours now, as several slots are now open!